L’atteso ritorno dei Dugongidi in Mediterraneo, dove vissero per milioni di anni, oggi tramite il Dugongo!

Quando di nuovo riavremo i Dugongidi in Mediterraneo?

Trepidante attesa del loro ritorno tramite il Dugongo!

L’atteso ritorno dei Dugongidi in Mediterraneo, dove vissero per milioni di anni, oggi tramite il Dugongo!

Ma che bello, trovo un gruppo di persone in un forum spagnolo che auspica, come me, il ritorno dei Sirenii Dugongidi in Mediterraneo dove vissero, pare dagli studi paleontologici, fino al Pliocene! Ecco il forum di questi virtuosi amanti spagnoli della rinaturalizzazione.

In particolare essi auspicano, come me, un ripopolamento da migrazione lessepsiana tramite il Canale di Suez per mezzo dei Dugonghi (specie di Sirenii) del Mar Rosso, che anche vivono nella aree egiziane settentrionali di quel mare. Quindi una popolazione molto prossima geograficamente al Mediterraneo.

Si auspica che la colonizzazione del Mediterraneo già in corso da parte di specie esotiche vegetali giunte dal Mare Rosso tramite l’artificiale Canale di Suez e le più calde temperature di questo nostro periodo interglaciale olocenico-antropocenico possano favorire l’estensione di areale del Dugongo, mammifero erbivoro, verso il Mediterraneo.

Se consideriamo l’areale odierno di diffusione del Dugongo, vediamo come sia ben possibile il suo passaggio in Mediterraneo tramite il Canale di Suez:

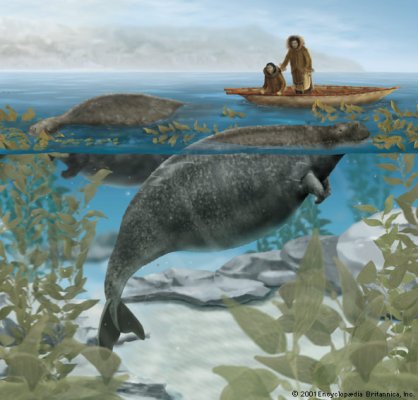

Tra le specie di Sirenii oggi viventi: il Dugongo (Dugong dugong), mostrato a sinistra, e tre specie di Lamantini.

Il nome dell’ordine Sirenia deriva proprio dalle sirene della mitologia del tipo pesce-donna umana con seni. Secondo una leggenda, infatti, in passato i marinai scambiavano questi animali per le sirene metà donna e metà pesce. Secondo altri il mito invece fu influenzato dalle foche.

Lamantini e Dugonghi odierni sono adattati ad acque calde tropicali.

Fino a pochi secoli fa viveva sulla Terra anche una ulteriore specie di sirenio adattata ad acqua fredde: “la Ritina o Vacca di mare di Steller (Hydrodamalis gigas) era un mammifero, ora estinto, appartenente all’ordine dei Sirenii. Fu scoperta nel 1741 dal naturalista tedesco Georg Wilhelm Steller nel Mare di Bering, tra Siberia e Alaska, e costituì anche l’ultima popolazione vivente di questo mammifero avvistata in natura. E’ probabile che un’altra popolazione sia sopravvissuta fino a tutto il 18° secolo nelle Isole Aleutine. Nel Pliocene e nel Pleistocene, la ritina occupava un’areale compreso dal Giappone a Baja California, in Messico, un’areale che coincideva con quello della lontra di mare Enhydra lutris“. Testo virgolettato e immagine seguente tratti da un articolo in rete:

L’estinzione della Ritina, con tutta probabilità causata dalla caccia e dalla pressione antropica più in generale, ci deve portare a questa accortezza: la caccia deve essere svolta con massima programmazione di cosa, quanto, dove e quando prelevare, non possiamo più permettere che avvengano questi stermini di nessunissima specie che poi danneggiano in primis i cacciatori stessi! Non c’è da fare troppi giri di parole, è la stessa cosa che mettersi a fare farina da tuttissimi i semi di grano prodotti nel raccolto di un anno, così l’anno dopo si semina nulla e si raccoglie nulla!

La Ritina apparteneva alla stessa famiglia dei Dugongidi ed era il più grande rappresentante vivente nel XVIII sec. d.C. dell’ordine dei Sirenii.

Quanto sarebbe importate pertanto dare ai Sirenii la possibilità di ritornare in Mediterraneo per la preservazione di questo suggestivo antico ordine di mammiferi e sue future evoluzioniste diversificazioni! Si allontanerebbe così anche sempre più il Dugongo dal rischio di estinzione offrendogli nuovi areali di potenziale espansione.

In Salento resti fossili proprio di Sirenii si ritrovano nella miocenica pietra leccese!

Ecco qualche dato in questo studio sui Sirenii del Terziario prima delle grandi glaciazioni del Quaternario in Terra d’Otranto, da cui estraggo questo passo:

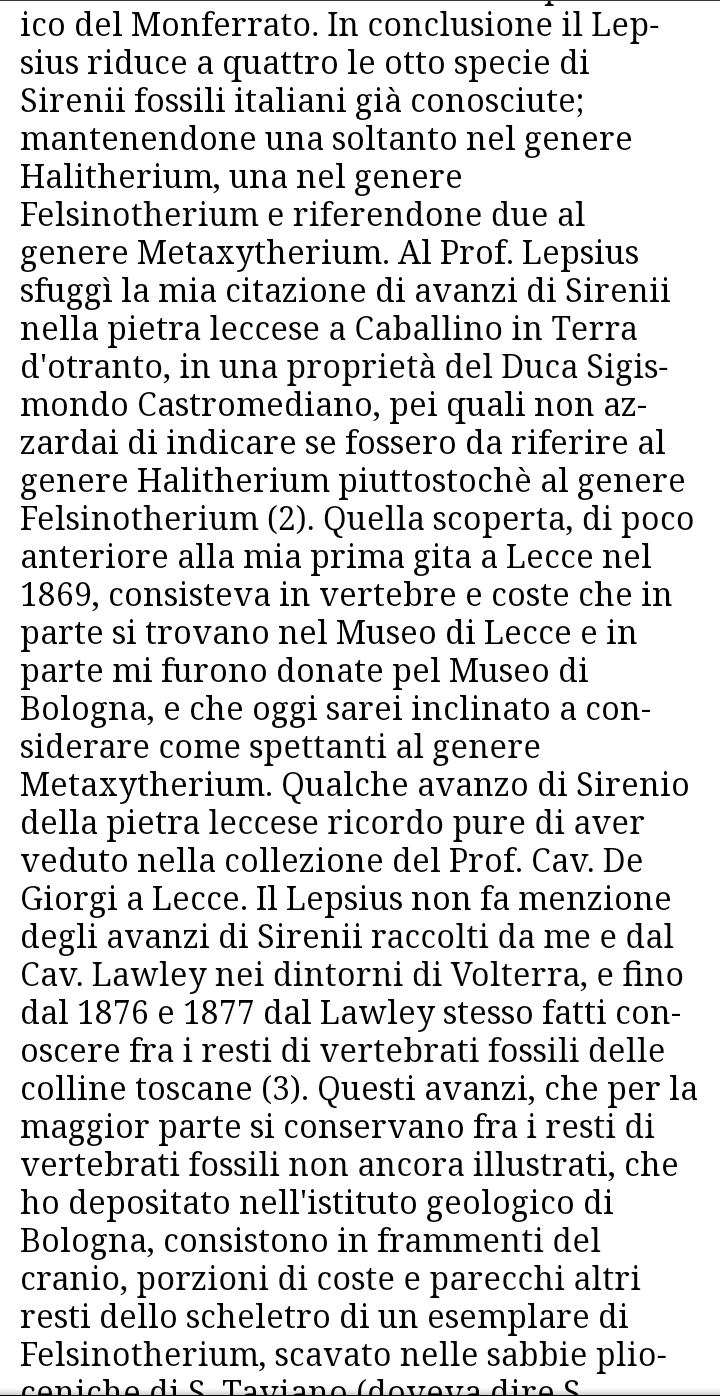

Illuminante questa ricostruzione in un post facebook della pagina “Animali e Piante fossili della Sardegna” che riportiamo in screenshot:

In Salento nella calcarea sedimentaria pietra leccese che è di origine miocenica ben sappiamo si ritrovano anche in maniera non rara grandi denti fossili proprio dello squalo Megalodonte (parente degli attuali Squali bianchi) che la paleontologia ha rivelato essere un predatore dei Sirenii del genere Metaxytherium.

I Sirenii del genere Metaxytheriumerano molto simili nella struttura all’odierno Dugongo, differivano sostanzialmente solo nella dentatura. Oltre ai soliti crani più o meno completi, di questi animali sono state ritrovate tantissime costole e questo perché le costole sono piene per permettere all’animale di resistere più tempo sott’acqua e con minore dispendio di energie durante i lunghi rifornimenti di alghe e piante acquatiche. È questa particolarità che ha permesso la grande conservazione di tante costole fossili.

Anche qui leggo dei Sirenii fossili nella pietra leccese miocenica del Salento, uno studio da cui estraggo il passo seguente:

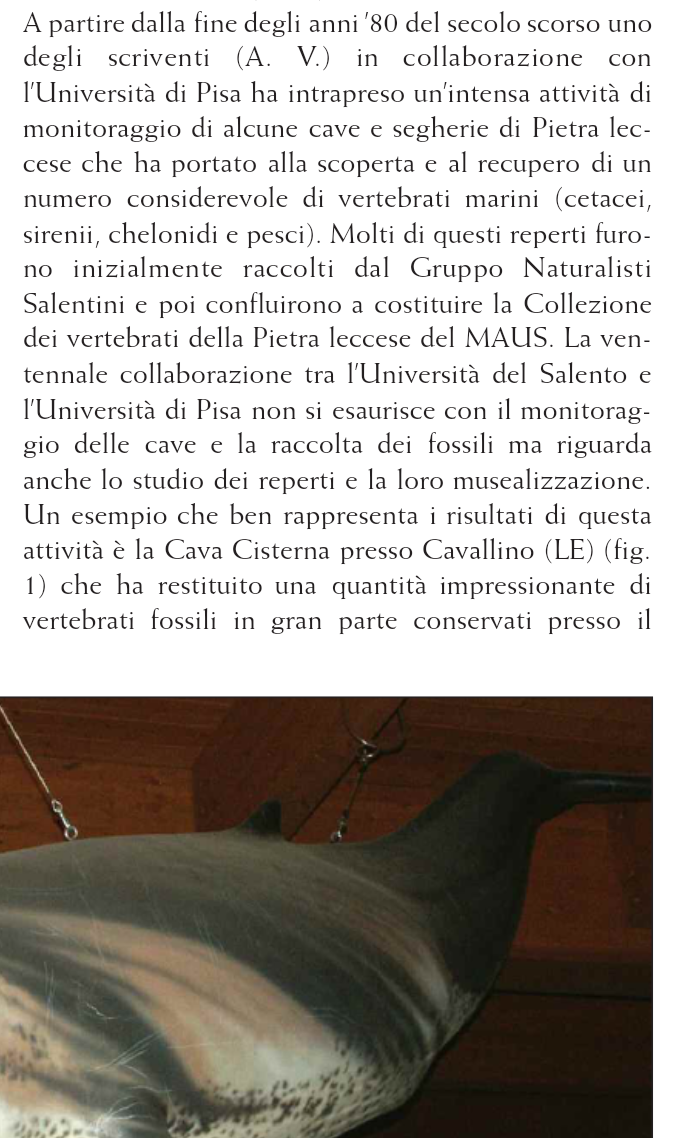

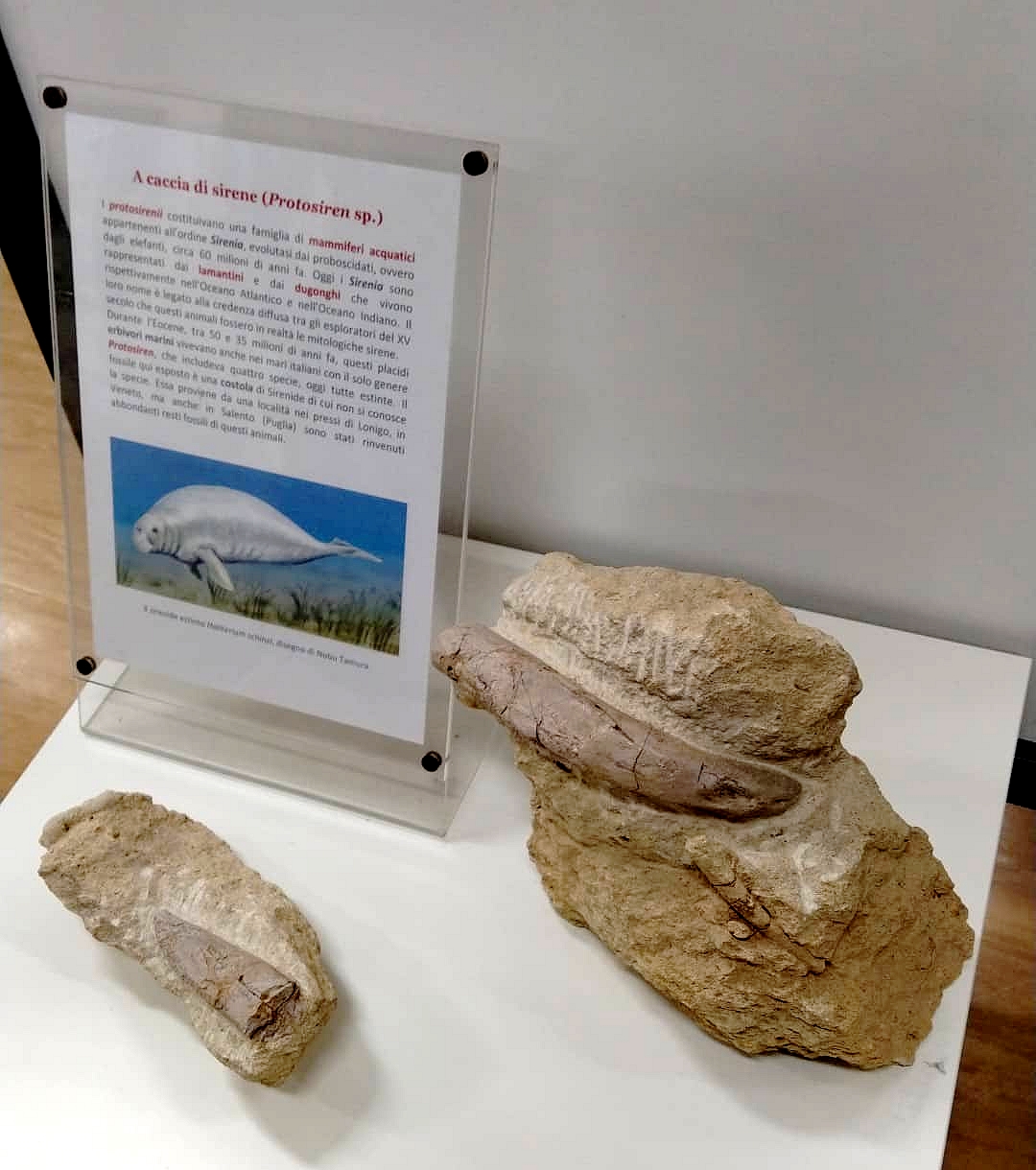

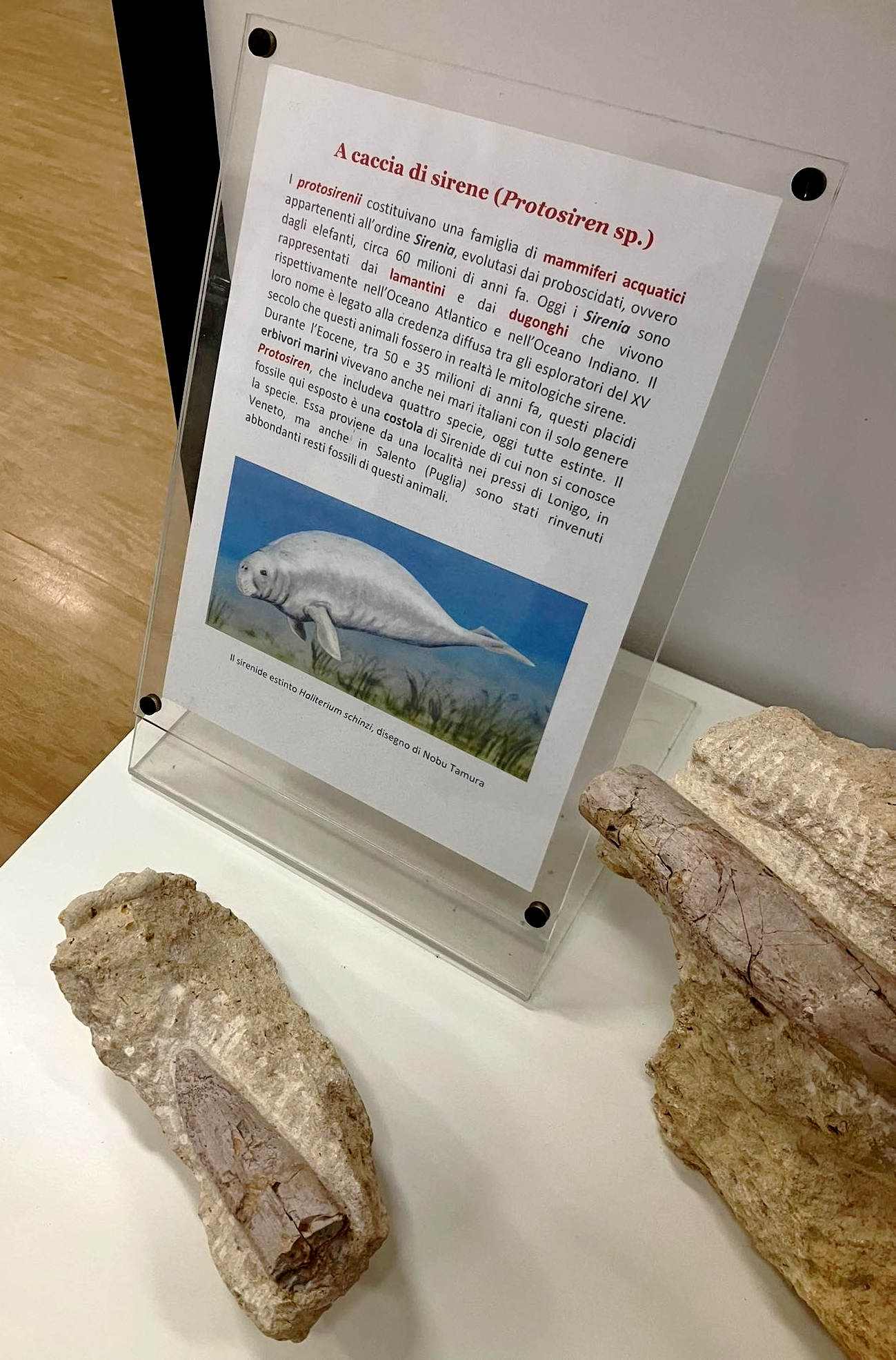

Visitando successivamente alla stesura di questo articolo il Museo delle Scienze della Terra nel campus del Politecnico di Bari il 19 dicembre 2022, ho notato la presenza in una teca di testimonianze fossili relative a Protosirenii rinvenute in Italia, Puglia inclusa:

Fossili di Sirenii anche son mostrati nel museo di Tropea in Calabria, ecc.

Leggiamo dunque del genere Metaxytherium, un genere di Sirenii estinto, ma appartenente alla famiglia dei Dugongidi ancor oggi sopravvivente con il Dugondo. Qui in questa ricca scheda che linko possiamo approfondire la interessante storia paleontologica di questo genere, Metaxytherium, strettamente legato al Mediterraneo e all’Italia. Motivo per cui una stupenda notizia sarebbe oggi il ritorno, seppur coadiuvato direttamente o indirettamente dall’uomo, della famiglia dei Dugongidi, tramite il discendente Dugongo, in Mediterraneo.

Nel Pliocene l’ultima specie di sirenio che visse nel mar Mediterraneo fu Metaxytherium subapenninum (Bruno, 1839), scomparve definitivamente dal Mediterraneo intorno a 3 milioni di anni fa per il progressivo raffreddamento climatico.

Dugongo.

Con l’apertura attuale del Canale di Suez occorre favorire la migrazione lessepsiana dei Dugonghi dal Mar Rosso dove vivono verso il Mediterraneo.

Acquari-zoo del Mediterraneo potrebbero anche partire da esemplari in cattività per progetti sperimentali di riproduzione e introduzione della loro prole in natura in Mediterraneo in prescelti siti giudicati più idonei ai Dugonghi dal punto di vista trofico e non solo.

Segnaliamo questo studio sui Dugonghi in Mar Rosso dove si spiega il concetto delle “piste di alimentazione” tracciate da questi pascolatori dei fondali.

Questo deve essere anche il modo ecosostenibile, senza razzismo verde e senza ecoterrorismo, con cui semmai si affronta la questione della diffusione in Mediterraneo di nuovi vegetali provenienti tramite il Canale di Suez dal Mare Rosso, con questo loro “predatore”, l’erbivoro Dugongo!

Oreste Caroppo 4 luglio 2021

ALLEGATO successivo

APPENDICE

The Past and Future of Sea Cows in the Mediterranean Sea

Were sea cows once found in the Mediterranean Sea? The answer is yes, but the better question is how long ago? A taxon related to the modern dugong, †Metaxytherium, was common in the Mediterranean sea until the end of the Pliocene, when the first of the Pleistocene glacial periods made conditions too cold for Sirenians (manatees and dugongs) and seagrass. Seagrass genera like Cymodocea, Zostera, and Posidonia, thought to have constituted the bulk of †Metaxytherium’s diet, eventually returned fro refugia to form the large seagrass meadows of the modern Mediterranean sea. Their original herbivores, however, have apparently been absent ever since, depriving the meadows of their most effective mediators and dispersers. It is possible, however, that said absence has not been unbroken, and that modern dugong (Dugong dugon) also inhabited the Mediterranean sea at one point, but the evidence for this is unclear.

Firstly, the point is moot unless we can establish that the Holocene Mediterranean sea could conceivably support dugongs. While the seagrass community differs in a few of its components from current dugong habitat, several of the genera present (ex. Cymodocea, Zostera) are eaten by dugongs elsewhere, and the rest (ex. Posidonia) do not occur in current dugong habitat so it is unknown if they would eat them. At least one genus of known sea cow fodder (Halophila) has become established in the Mediterranean sea through colonization via the Suez Canal. The absence of Halodule seagrasses is notable, as these make up the bulk of the dugong diet in some areas, but hypothetical Mediterranean dugongs may very well have exploited other vegetation in their stead. Dugongs also display omnivorous tendencies, occasionally eating molluscs and other invertebrates.

Water temperature is also a consideration, as dugongs can suffer from Sirenian Cold Stress Syndrome (SCS) after prolonged exposure to waters that fall below ~17 degrees Celsius. While some areas of the Mediterranean sea drop below this temperature in the colder months, this is not always the case. The waters around Alexandria, Antalya, Larnaca, Limassol, and Tel Aviv have an average temperature of 17 degrees Celsius during February and March and are much warmer the rest of the year. Athens, Gibraltar, Heraklion, Málaga, Malta, and Naples experience slightly cooler but comparable water temperatures. Some areas in the northern Mediterranean would likely be unsuitable in the winter such as the coastal areas of Barcelona, Marseille, Valencia, and Venice. Overall, the southern and eastern areas of the Mediterranean seem the most climatically suitable. It is worth noting that dugongs can alleviate the effects of cold temperatures by simply moving to warmer ones, which is common behaviour for Sirenians living in the cooler parts of their current distributions. Losses from SCS do occur but not often enough to significantly affect the population as a whole. With current climate trends, it is also quite likely that the Mediterranean sea will become warmer.

Judging by climate and vegetation alone, the answer to whether or not dugongs could live in the Mediterranean today and in the earlier Holocene is probably yes. If they did occur there, it is likely due to human activity that they no longer do. However, it has still not been established whether or not they did. The Holocene distribution of the dugong was certainly greater than in modern times, with remains turning up in Victoria, Australia, over 250 leagues away from the current extent of its Australian distribution in north-eastern NSW. Interestingly, the waters of southern Australia have also produced †Metaxytherium fossils, have a cooler average temperature (though it was likely much warmer at certain points in the Holocene), and are the only place in the world besides the Mediterranean to have native species of Posidonia. No Holocene remains of dugongs have yet been found in the Mediterranean, but there is speculation that accounts of mythical creatures from ancient history may have been inspired by encounters with this species. The sirens of ancient Greece, depicted in the Hellenistic period as half woman and half fish, may have been inspired by a local population of dugongs, just as manatees may later have given rise to stories of mermaids in the Caribbean. If there is a connection it may also have been inspired by dugongs from the Red Sea, however, where they still persist. While I have found many articles reporting the previous existence of dugongs in the Mediterranean, I cannot find a single verifiable reference for this.

So the answer to whether or not modern dugongs existed in the Mediterranean is, it would seem, probably not. More evidence will need to be acquired before we ever know for sure. Seeing as †Metaxytherium was quite likely the last of the Mediterranean Dungongids, and it barely made it into the Pleistocene, it might be a little out of range for typical trophic substitution. However, it is true that its niche remains empty, and that the seagrass community of the Mediterranean evolved alongside grazing Sirenians. This is certainly not an extinction that can be attributed to human activity, but it would seem that the causes behind †Metaxytherium’s extinction are no longer in effect, and human activity may be pushing the climate of the Mediterranean into something not unlike what it was in the Pliocene. Even if we never did a purposeful introduction of modern dugongs to the Mediterranean, it is worth noting that, much like some of their food species, they now have a possible migration route with which to translocate themselves. To my knowledge, dugongs are yet to attempt travel through the Suez Canal, but if they did so successfully, it might not be such a bad thing to look the other way. Their potential to reinvigorate seagrass communities and potentially control introduced vegetation from the Red Sea could be very valuable.

Dugong tourism could also be huge if properly invested in. I for one would love to go snorkelling in the seagrass meadows of Crete or Cyprus, complete with newly arrived dugong and returning monk seals (Monachus monachus). Manatees draw lots of visitation and conservation funding in Florida and the Caribbean and perhaps dugongs could do the same in Europe. Not only we would be creating a new population for an endangered species and returning the trophic effects of herbivory to the Mediterranean seagrass ecosystems, but we would also potentially be creating a new source of revenue for some of the lower income regions of Europe by providing them with an environmentally useful flagship species on which to build an ecotourism industry. Unlike seals, dugongs do not eat fish, potentially mediating conflict with local peoples, though there might be problems with net entanglement. The risk to the dugongs themselves would be much greater, being vulnerable to environmental destruction, pollution, and collision with boats. If dugongs did enter the Mediterranean, there would need to studies done on how local people might be affected and on how dugongs might be harmed by human activity.

More research is really the answer here. Firstly, we need to establish whether modern dugongs were native to the Mediterranean sea and whether it represents usable habitat for them. Secondly, we should determine whether they might be environmentally beneficial regardless of native status, i.e. a native family/niche if not a native species. Thirdly it should be investigated whether they might colonize the Mediterranean sea on their own power now that they potentially have an available route. Lastly, potential conflict for and benefit from dugongs to people living in the Mediterranean sea should be explored. I would be interested to know where the claim of an extinct Mediterranean population came from, because I might be missing something. If I am not, however, the possibility of dugongs in the future Mediterranean ecosystem is not so much a matter of correcting human impact, but experimenting with an idea that may prove beneficial to us, the dugongs, and to the environment. In a rapidly changing world, where novel ecosystems are quickly becoming the norm, it is useful for us to find inspiration from what has worked for similar ecosystems in the past, and to plan accordingly.